A pod of blue whales weaves through Pacific waters, each slender body exceeding the largest dinosaur.

A humpback enchants the ocean as his midnight melody travels for miles.

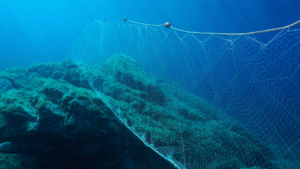

A nylon trap twists around a right whale, anchoring her underwater. Eventually, fishermen in pursuit of a different species find and discard her body to the dark sea.

Commercial fishing is one of whales’ greatest threats through bycatch—the unintentional capture and entanglement of nontarget species.

Whale Bycatch by the Numbers

Commercial fishing drops enormous nets and scatters hundreds of thousands of traps across whales’ feeding grounds and migration routes. What was once an undisturbed journey through open ocean has become a nearly undetectable maze. At least 300,000 whales, dolphins, and porpoises die every year after entanglement in fishing gear. That is equivalent to 800 deaths each day.

And that’s just the death toll we know.

Monitoring industrial fishing is challenging since it takes place so far offshore. This means some marine life mortality is unchecked. Several whales die out at sea, out of sight, and off the record.

Still, many researchers are working to uncover the extent of bycatch. We now know as many as 80% of right and humpback whales have been entangled in fishing gear at least once. The commercial fishing industry is the number one threat to endangered populations like North Atlantic right and Arabian Sea humpback whales. Researchers once assumed large whale species, such as blue and fin, mostly avoided whale bycatch since they are stronger and live farther offshore. However, we now know about 60% of blue whales and 50% of fin whales in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence show evidence of entanglement in nets. It seems no whale is safe from the fishing industry’s reach.

The Immediate Costs of Whale Bycatch

Death by bycatch is tedious. If fishing gear wraps around a whale’s mouth and prevents feeding, they starve. Gear can anchor a whale underwater. Unable to reach the surface to breathe, they drown. Some whales escape entanglement only to succumb to infected wounds.

A less tragic, but still critical, consequence of entanglement is stress. Even short entanglements affect whales’ behavior, energy, and susceptibility to disease. Some entanglements last for months, even years, with a whale hauling gear that won’t detach. One example is commercial lobster traps that have a buoy on the surface with a vertical rope extending down to cages on the seafloor. A whale who swims through an area with these traps may wind up with rope around their tail and a cage to carry, perhaps for the rest of their life. While this accidental cargo may not constrain them, it does force them to expend more energy simply to swim. This is especially significant for a female whale. She may have too little energy left to successfully reproduce.

What Ecosystems Stand to Lose

If whales aren’t safe, neither are their ecosystems. These animals support layers of life in the ocean, and it would be catastrophic to lose them.

Ocean mixing is the process by which nutrients and heat are distributed throughout water. Marine vertebrate activity alone generates one third of all ocean mixing. They are nearly as powerful as tides and wind. Whales contribute by creating a vertical “whale pump.” Each time they dive and resurface, they move nutrients that may otherwise be stuck in deeper water, or even the ocean floor, closer to the surface. In this way, whales support organisms ranging from aquatic plants to sea birds. They also move nutrients horizontally across the ocean during their migrations.

In addition to ocean mixing, whales release fecal plumes rich in iron, nitrogen, and phosphorous–all necessary nutrients for phytoplankton. These microscopic marine algae are the foundation for marine food webs. The boost whales give phytoplankton populations ripples across entire food webs to krill, fish, and large mammals including other whales. And people. Our seafood availability depends, in part, on whales.

Another, perhaps more surprising, service whales provide is curbing climate change. Phytoplankton are photosynthetic, so they absorb carbon dioxide. When they die, 20-40% of the carbon inside them sinks to the ocean floor. Therefore, by increasing phytoplankton stocks, whales increase carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere and storage under the sea. Additionally, when whales die and settle to the ocean floor, their bodies act as massive carbon stores with slow rates of decay. If recovered to pre-industrial populations, large baleen whales could have the carbon storage capacity of 110,000 hectares (about 272,000 acres) of forest.

Whales are unquestionably important to their ecosystems. Even in places such as the Southern Ocean, where whale populations were decimated but are now recovering, the local food web is still reeling. If whale bycatch continues, or worsens, how many more places will suffer? How do we help?

Reducing Whale Bycatch

New fishing technology is one strategy to decrease whale bycatch and entanglement. Some lobstermen are now using traps that either release a vertical line through the water column only during retrieval or float to the surface with no line involved at all. This eliminates the entanglement danger.

Many fishermen and industry stakeholders are hesitant to spend the time and financial investments required to transition to this and other new technology. Their livelihoods are on the line. Nations have an obligation to enforce safer fishing strategies and an opportunity to support workers through the transition by subsidizing new technology. This will likely require a new tax bill. While a tax increase is uncomfortable, there is a much bigger cost involved. Without industry-wide changes, some species, such as North Atlantic right whales, will likely be entangled to extinction.

We can also reduce whale bycatch by going straight to the source. Our current global seafood consumption exceeds all sustainability quotas. Dramatically decreasing this demand is crucial to whale, and all marine, conservation.

It’s important to remember, for most of us, we merely desire fish. The ocean requires whales. They move nutrients, support the food web, and curb climate change. All we have to do is let them live.

Since whales and the fishing industry exist internationally, we need international action. As an individual, it can be intimidating to demand the world look out for its whales. Fortunately, many organizations are already devoted to protecting them with campaigns, trainings, and other resources open to any ocean ally. Just as whales can support the lives of countless ocean creatures, together we can ensure the safety of entire whale species.

Report Entangled Whales in the United States

- 1-877-SOS-WHALE (767-9425)

- United States Coast Guard on VHF CH-16

- Dolphin and Whale 911 app (for Apple devices)

- NOAA Fisheries (listed by region)

Report Stranded Whales Across the World

- Save the Whales (listed by country)

Sign Petitions

- Change.org (Seaspiracy Petition)

Support Organizations

Submit Comments

- International Whaling Commission

- Your national and local lawmakers

Want to learn more about ocean conservation? Read our article about shark overfishing.

Sources

- “A Whale of an Effect on Ocean Life: The Ecological and Economic Value of Cetaceans.” Animal Welfare Institute, 2017, https://awionline.org/awi-quarterly/fall-2017/whale-effect-ocean-life-ecological-and-economic-value-cetaceans

- Briggs, Helen. “Whale threats from fishing gear ‘underestimated.” BBC, 9 Feb. 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-55987350

- McCarthy, Joe. “Endangered Whales Are Being Killed by Fishing Gear. New Technology Could Change That.” Global Citizen, 8 Nov. 2019, https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/endangered-right-whales-fishing-gear/

- “Threats.” WWF, https://wwf.panda.org/discover/knowledge_hub/endangered_species/cetaceans/threats/

- “Whale Entanglement – Building a Global Response.” International Whaling Commission, https://iwc.int/entanglement

- Zuckoff, Eve. “Ropeless Lobster Fishing is Good News For Endangered Whales.” NPR, 19 Feb. 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/02/19/969559244/ropeless-lobster-fishing-is-good-news-for-endangered-whales