Understanding the Organic Label

Alexandria Williams

Whether they be in the local supermarket or co-op, food items everywhere contain a “green” slogan. Consumers find themselves bombarded with different labels all claiming to be “natural”, “organic”, “non-GMO”, “ecofriendly”, and “sustainable.” But what does it all mean? Unfortunately, if you start looking for the truth behind the labels, you uncover the spirit of a movement meant to liberate the food system from toxins no longer runs counter to industrialized agriculture.

Organics are not new to consumers. They rose in popularity in the 1990s and soon became regulated by the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). Organic practices, as defined by the USDA, include practices based in breeding without GMOs, pest management without pesticides, natural fertilizers instead of synthetic ones, open space for animals, and no hormones or unnecessary antibiotics. The USDA issues organic certification to growers at a cost after three years of implementing organic practices.

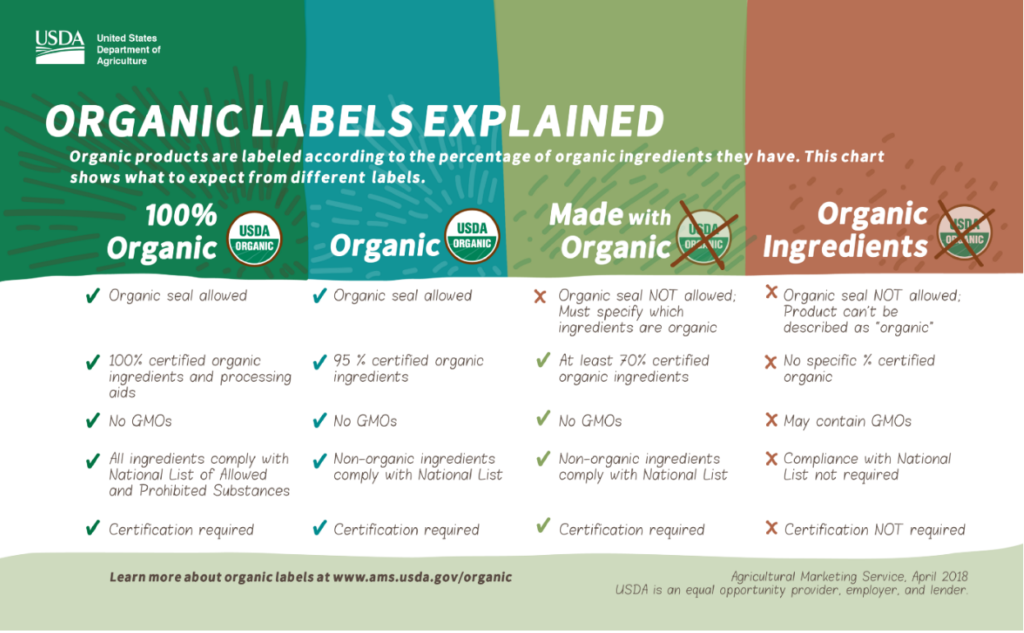

There are four labels for organic foods, but only two are allowed an organic certification: “100% organic” and “organic.” The latter means 95% of a product’s ingredients are organic, but the processing aids are not. Processing aids are additives that simply improve product quality or lengthen shelf life. The other two labels are “made with organic” and “organic ingredients.” Neither qualify for a USDA certification.

Organic Label Distinctions. Image: USDA

Most consumers already have their own foggy assumptions about what organic means, without the added confusion of multiple labels. It seems “organic” does not mean just one thing.

What was organic supposed to mean? Initially, the organic movement aimed to reduce pesticide use in foods.

The USDA created the National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances. It’s important to ask, what about the unknown substances and the untested substances? To elaborate, the oil industry profits off the lack of research into the different forms of hydrocarbons (petroleum) and the harmful effects of these chemicals. The point, even with regulation, it is difficult to micromanage corporations and protect against their objective of profit maximization, which has been proven to be at the expense of the consumer.

In a market where consumers are willing to pay a premium price, large-scale corporations have cashed in. Rather than finding purpose in doing a social good, it became a matter of economic motivation. While decisions based in economic benefit should not be shunned, corporate’s history of greenwashing amidst the green movement brings their involvement into darker waters.

Greenwashing refers to the advertising scheme in which business’s claim to sell environmentally friendly products. In a 2021 website screening of online markets for greenwashing, the European Commission and national consumer authorities found 42% of claims to be exaggerated, false, or deceptive, and in 59% of cases, evidence to back claims was difficult to find. Corporate involvement in the green movement has been far from trustworthy, casting doubt on their participation in organics.

In Greg Northern’s 2011 journal, “Greenwashing the Organic Label”, he describes corporate’s propensity to spend on advertising rather than substantive change in order to reap the benefits of premium prices. This attitude is captured in a statement by General Electric’s global executive director of advertising and branding: “Green is green as in the color of money. It is about a business opportunity, and we believe we can increase our revenue behind [our] products and services.” Corporations are sinking their teeth into consumers’ wallets with each bite taken by organic consumers.

The Cornucopia Institute, a non-profit auditing and investigating organic labels, warns against this relationship, which they’ve termed, “Big Organic”. As they see it, Big Ag’s involvement undermines the spirit and integrity of the organic movement. Big Ag refers to, “all farms are owned by major corporations, which also control the nation’s (if not the world’s) supply of seeds, plants, food, machinery and land”.

Problems begin once farms are neither committed nor driven by the purpose or goals of the organics movement, as is the case with Big Ag. In an article discussing the validity and maintenance of organics, Keith Carter says, “advocates say factory farm operations that use organic feed but confine thousands of chickens or cows into cramped indoor spaces do not meet the standard, but those farms are continually approved for certification”. Thus, the organic label is called into question.

In assessing Simple Truth, Kroger’s organic brand, the previously mentioned Cornucopia Institute references how the, “…variability in product sourcing makes it difficult, sometimes impossible, for consumers to determine where and how the products” were produced. Meaning, considering the lack of transparency, organic agriculture could be produced on giant factory farms. Ironically, a report by Business Insider in 2015 revealed Simple Truth reached $1 billion in sales in just two years. Just as Northern understood in 2011, the corporate sector is capitalizing on prices without substantial change.

O Organics Label. Image: Albertsons Companies

Davis’ own supermarket, Safeway, is clouded with a lack of transparency. Their O Organic label for eggs, poultry, and dairy products all received the lowest score citing an inability to confirm organic practices and unknown sourcing.

Lax standards are not isolated problems, the threat of monopolization also looms over the movement as well known organic brands have been claimed by Big Ag: General Mills owns Annie’s Homegrown, Coca-Cola owns Honest Tea, and Pepsi owns Naked Juice. Four firms control all of the organic industry in Canada and the US.

Lisa Clark, a research associate at University of Saskatchewan states organics is no longer, “a counter movement to industrialized agriculture’s devaluation of social and environmental relations in the production process.”

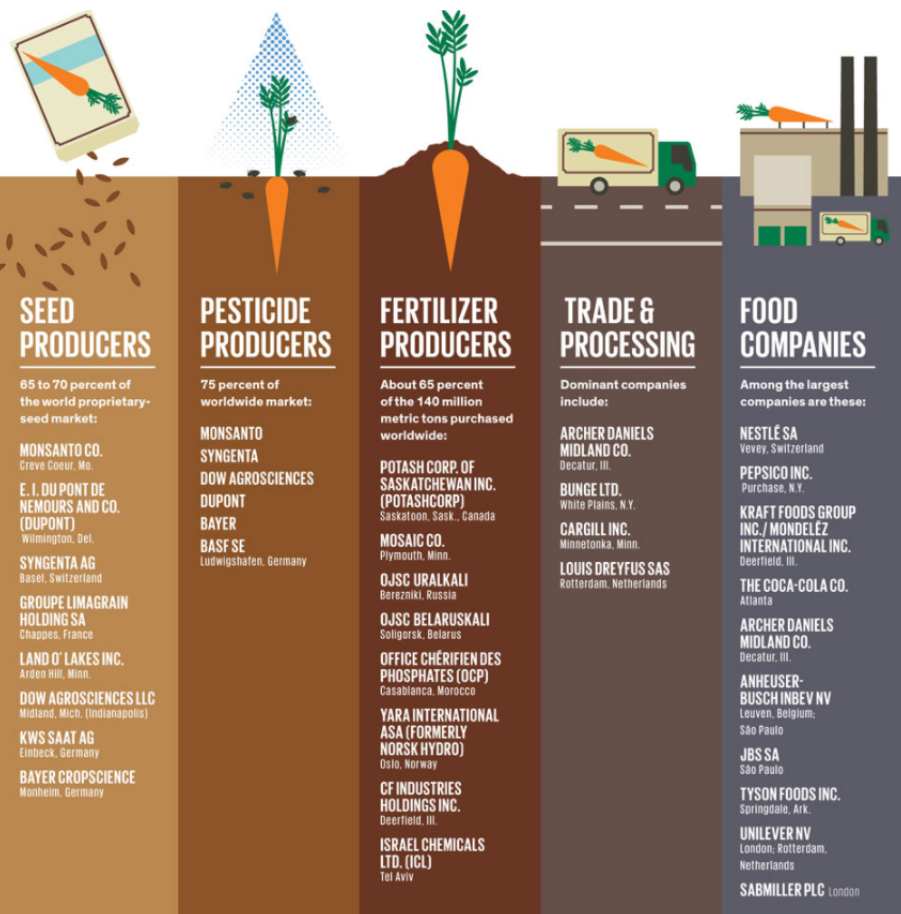

This type of control and standardization is Big Ag. For example, seven companies produce 70% of seed products in the world market and six companies produce 75% of pesticides in the market.

Mapping Big Ag. Image: James Provost

John Ikerd, author of the 2008 book Small Farms Are Real Farms: Sustaining People Through Agriculture, stated: “Once these large agri-food corporations gain positions of influence, they’ll attempt to eliminate competition by creating complex regulatory requirements that smaller producers cannot meet — or can’t meet as efficiently. This is nothing new.” Industrial Agriculture is fueled by the competition ingrained in the capitalist market, but the stamping out of fellow farmers and local producers is where it comes in conflict with the spirit of the organic movement.

Remember the certification fee, unfortunately, small scale growers face barriers to entry due to the cost of not only the fee, but the process. Farmers must engage in organic growing practices for three years before they qualify, meaning the cost of expensive seeds and additional labor cannot be offset with premium prices. As a result, small scale growers have been turned off from the process, emphasizing their, “product as local first and organically grown second”.

Cornucopia’s Executive Director recognizes buyers come not only for what the food doesn’t contain, but also, “think they are doing something good for society, animal welfare, soil health and economic justice for the small family farmer.” If buying organic is a means to environmental justice, consumers ought to be wary.

The solution, purchase from co-operatives or local farmers markets rather than supermarkets if, as a consumer, your goal is a more sustainable food system. A 2015 study by the Organic Trade Association showed 78% of organic buyers, “shop at conventional food stores and supermarkets.” Organic buyers are engaging the system of Industrial Agriculture without fully realizing it. As Organic Trade Association sues the USDA for failing to put in place new organic livestock standards, arm your wallet and choose selectively..

Disclaimer: The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the various authors and forum participants on this web site are their own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of SAFE Worldwide.